CMS prioritizing healing heart valves over bolstering brain health

By Andrey Ostrovsky & Everett Crosland

In August 2020, the nation’s largest health insurer, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), proposed its Medicare Coverage of Innovative Technologies (MCIT), which intended to provide national Medicare coverage on the same day as Food and Drug Administration (FDA) market authorization for breakthrough devices. The Breakthrough Devices Program at the FDA accelerates the approval or clearance process for certain medical devices that provide for more effective treatment or diagnosis of life-threatening or irreversibly debilitating diseases or conditions. Building on the Breakthrough Devices Program, MCIT could have shortened the time to market for breakthrough-designated devices (BDD) that could meaningfully improve patients’ lives.

After the transition to the Biden administration in November 2021, CMS repealed MCIT, one of the few helpful Trump-era rules. But after sharp industry and provider criticism, CMS announced listening sessions to get feedback on a replacement for MCIT called Transitional Coverage for Emerging Technologies (TCET).

In a STAT article I (A.O.) wrote last year, I argued that MCIT could meaningfully help eliminate disparities in treatment for Medicare beneficiaries and balance accountable chronic disease management with the need for social distancing in the Covid-19 era and beyond. Whether it’s called MCIT or TCET, it is imperative that CMS create an expeditious process to cover innovative devices that benefit Medicare patients and close health equity gaps, one of the main priorities of the CMS administrator, Chiquita Brooks-LaSure.

We have conducted an analysis to help CMS design TCET so that it can reduce inequities in reimbursement for BDDs, especially those focused on brain health, one of the main priorities of President Biden according to his State of the Union (SOTU) address.

To characterize and quantify the disparities against brain health in the approval and coverage of BDDs, we performed a Google search for Expedited Access Pathway (EAP) and BDDs beginning in 2015 through March 2022. We aggregated the findings into a spreadsheet and categorized the BDDs that were FDA approved or cleared, were reimbursed by CMS, whether they were digital therapeutics or diagnostics, whether they focused on behavioral health, and, as a comparator, whether they focused on cardiac health. As an external source of validation, we referenced this list against that of the Medical Device Manufacturers Association, with comparable results.

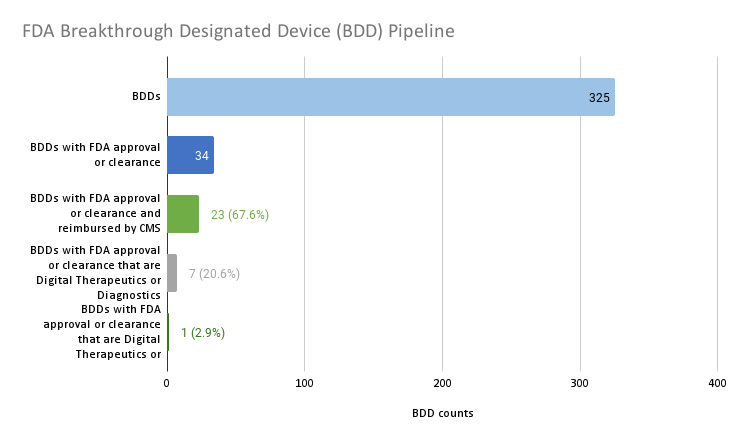

Source: Author analysis.

To date, 325 devices have been granted breakthrough designation. This analysis highlights that one of the challenges that MCIT was intended to overcome — the bottleneck of determining whether or not Medicare should cover FDA cleared or approved BDDs — is not much of an impediment to innovations reaching the market. Only 34 of the 325 BDDs, or about 1 in 10, gained FDA market authorization. And the majority, or 23 (67.6%) of the 34 BDDs with FDA market authorization, have Medicare reimbursement. There does not appear to be much of a backlog of BDDs that have achieved FDA market authorization but failed to achieve coverage.

Yet a critical issue remains that TCET could solve: There is a growing disparity in reimbursement of one class of product versus another and in reimbursing treatment and diagnosis of one disease state versus another. Only seven (20.6%) of the 34 BDDs with FDA market authorization are digital therapeutics or diagnostics. The single (2.9%) digital diagnostic that is reimbursed is for a somatic or physical condition, while the remaining digital therapeutic and diagnostics are not reimbursed and they focus on behavioral health or neurological specialties.

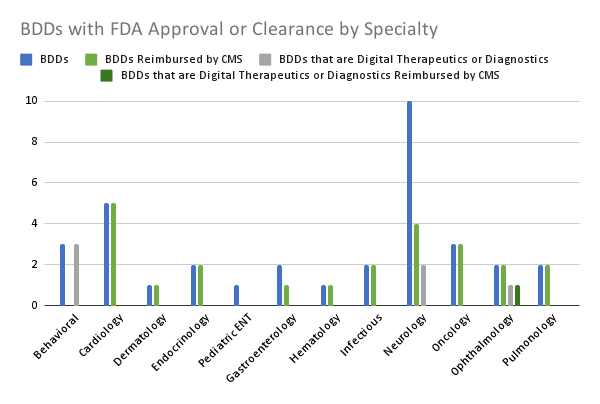

Source: Author analysis.

Digging deeper into the data, we found even more profound product class and disease state disparities. The vast majority (19 of 20, 95%) of the FDA approved or cleared BDDs that are in somatic or physical health specialties for adults are reimbursed by Medicare. Only one of the 20 (5%) of these devices was a digital therapeutic or diagnostic and it was reimbursed.

In contrast, only a fraction (4 of 13, 30.7%) of the FDA approved or cleared BDDs that are in behavioral health or neurology specialties are reimbursed by Medicare. Five of the 13 (38.5%) of these devices are digital therapeutics or diagnostics and none of them are reimbursed.

Five out of five (100%) FDA approved or cleared BDDs focused on cardiology are reimbursed by Medicare. Zero out of five (0%) FDA approved or cleared BDDs focused on behavioral health or neurology are reimbursed by Medicare. Put another way, CMS is prioritizing healing heart valves over bolstering brain health.

Digital therapeutics and diagnostics may enable patients and families to overcome barriers inherent to brick and mortar care such as transportation issues, long wait lists, and systemic racism among providers. CMS should ensure that breakthrough-designated digital therapeutics and diagnostics have an accelerated pathway to reimbursement through TCET so that the rule does not conflict with the intent of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, the CMS Administrator Brooks-LaSure’s focus on closing health equity gaps, and President Biden’s SOTU charge to improve brain health.

For CMS to avoid violating mental health parity laws and going against its own priorities, it will need to reconcile its historical critiques of MCIT. Most notably CMS leaders are concerned that under MCIT, CMS could have covered devices without adequate evidence to treat the Medicare population.

One way to address Medicare-specific evidence needs is to grant provisional coverage and reimbursement for BDDs with FDA market authorization during the transitional coverage period while the manufacturer develops additional evidence specific to Medicare populations. This approach can help balance equitable access to care with the need for evidentiary support.

CMS leaders’ concerns about MCIT’s evidence limitations in Medicare populations bring up another impediment to this administration reaching its equity goals. Commercial, Medicaid, and exchange insurance carriers rely on Medicare coverage determinations for many of their own medical policy decisions. Devices that fail to get Medicare coverage will lack the HCPCS codes needed for coverage with other payers. This means that BDDs with FDA market authorization serving children and adults under 65, especially those in poverty, are systematically not getting covered.

To address the Medicare coverage roadblock for commercial, Medicaid, and exchange insurance carriers, CMS could create modifiers for HCPCS codes that designate which populations certain codes could be applied to, such as pediatric populations and adults under 65.

Including HCPCS code modifiers may not be enough for TCET to address CMS’s current coverage disparities. TCET should call for the Center on Medicare to improve internal processes so that there is more expertise and prioritization on brain health and non-Medicare populations. With subject matter experts on these topics in the Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services (CMCS) and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), TCET should require that leaders in the Center on Medicare more routinely collaborate with CMCS and CMMI leaders on coverage determinations.

Despite all of these critiques, we have to give the Center for Medicare credit because they did finally open the door for digital therapeutics coding by approving the HCPCS Level II code A9291 for “Prescription digital behavioral therapy, fda cleared, per course of treatment.” However, Medicare still doesn’t reimburse this code and this code lacks the specificity needed for most commercial insurers to systematically reimburse all brain health focused digital therapeutics.

Medicare also has made productive strides in providing reimbursement for the new CPT code 989X5 for “Remote therapeutic monitoring,” which could be used by some digital therapeutics for reimbursement. However the reimbursement amount is anemic and is mostly limited to musculoskeletal and respiratory indications.

This analysis demonstrates that CMS’s coverage processes demonstrate product class and disease state disparities. These disparities contradict mental health parity statute, CMS Administrator Brooks-LaSure’s focus on equity, and President Biden’s charge to improve brain health. TCET can help close these gaps by granting provisional coverage for BDDs with FDA market authorization with evidence development, creating modifiers for HCPCS codes for non-Medicare populations, and requiring the Center on Medicare to incorporate experts from CMCS and CMMI into coverage determinations.

Andrey Ostrovsky is a pediatrician, managing partner at Social Innovation Ventures, former chief medical officer for the Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services, and a strategic advisor to the Digital Therapeutics Alliance.

Everett Crosland is the Chief Commercial Officer at Cognito Therapeutics and board member of the Digital Therapeutic Alliance.